return to About

JESUS FINDS HIS WAY TO TEXAS

Exclusive from WND.com: Marisa Martin spotlights artwork of James JanknegtPublished: 01/10/2014 at 10:08 AM

author-image MARISA MARTIN About | Email | Archive

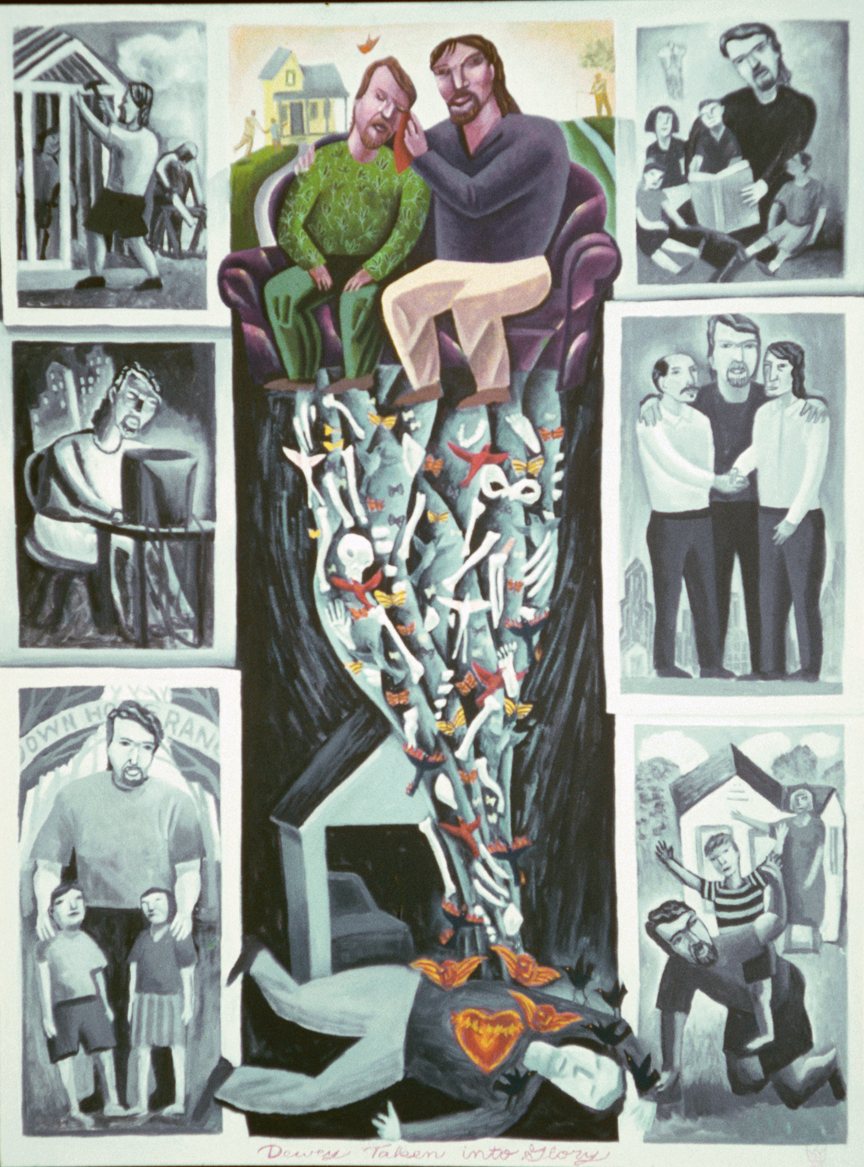

"Dewey taken up into Glory" by James Janknegt

When a young father and husband took his own life in 1999, an entire city mourned and searched for comfort. High-tech whiz kid and teacher Dewey Winburne was eulogized, pondered and thanked for his contributions to Austin, Texas, by the press and a multitude of persons.

One left grieving was painter James Janknegt, who quietly sought comfort in his art. Janknegt and Winburne had been friends and members of the same church with many common interests. While struggling with the “huge negative impact” of Winburne’s act on his family and community, Janknegt set to memorialize him anyway.

Janknegt faced a formidable task of love laced with theological and moral pitfalls. His painting “Dewey Taken up into Glory” focused on relationships and the irreplaceable investments of a man’s life and time. A central panel ascends away from death and darkness to a symbolic, heavenly settee, seated with Christ himself. He wipes away all tears with a red handkerchief.

Art commemorating death of any kind is rare in the West now, with the exception of occasional celebrities like Lady Diana or Elvis. Generally secular, they stick to laudable accomplishments, good deeds and earthly hagiography of the deceased – or their extreme photophilia.

Floating ribs and jawbones brighten “Dewey,” implying relics of the saints. No accident. Over 30 years Janknegt has migrated toward an art that is faithful to Christian tradition by “relying on visual image to enhance the experience of prayer.” Traditional intent, perhaps, but he reinterprets the images with very modern terms and flavor.

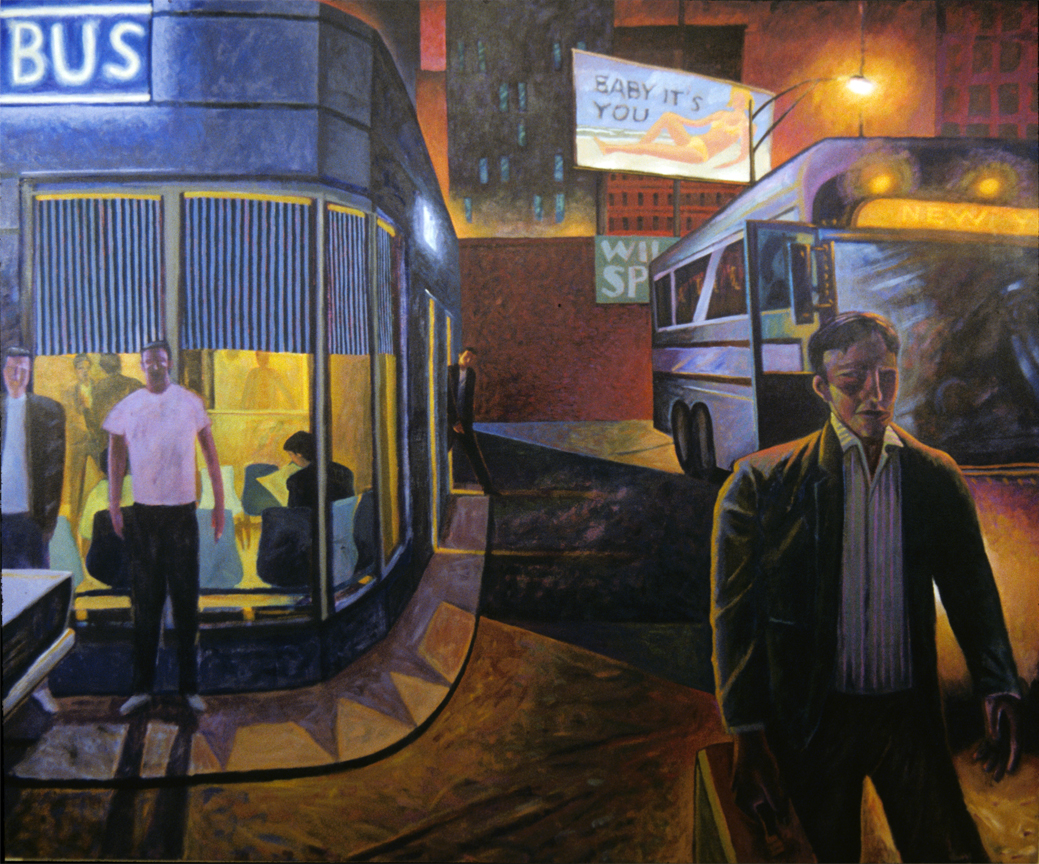

Some of Janknegt’s pieces from the 1980s are reminiscent of Edward Hopper – in spirit if not explicitly. Solitary figures pass through bleak, impersonal landscapes and detached city scenes. Flat planes, jarring colors and shriekingly high-contrast shadows inhabit his paintings from this time. Janknegt displays true genius when he works with architectural elements and details, planes and dramatic lighting – where he creates scenes of great intensity although there may be no figures or action.

Luminous signs clearly mark these pieces, but figures stay ironically detached and uninvolved. Such is “Star Inn,” an obvious reference to the nativity story, but situated in an unsavory area beneath a freeway. The neon “star” is the only real light in this forbidding scene.

Janknegt offers that periodic changes in his painting style are a parallel “biography of my life.” Challenged to work from his “gut” after a divorce, he began using dark cityscapes as a projection of his own emotional state and the state of the entire world. Jesus is painted into these night sessions like a startling flare, a signal to stop and look again.

He built up his own iconography, newly coined yet easily identifiable for viewers. In “Father Forgive Them – Good Friday” fighter jets crown a weary Christ, who looms over the city. Skies are similarly menacing with dark figures about to burst into tangibility. Prostitutes, killers and the monetarily obsessed stroll through fractured and dismal cubist cities.

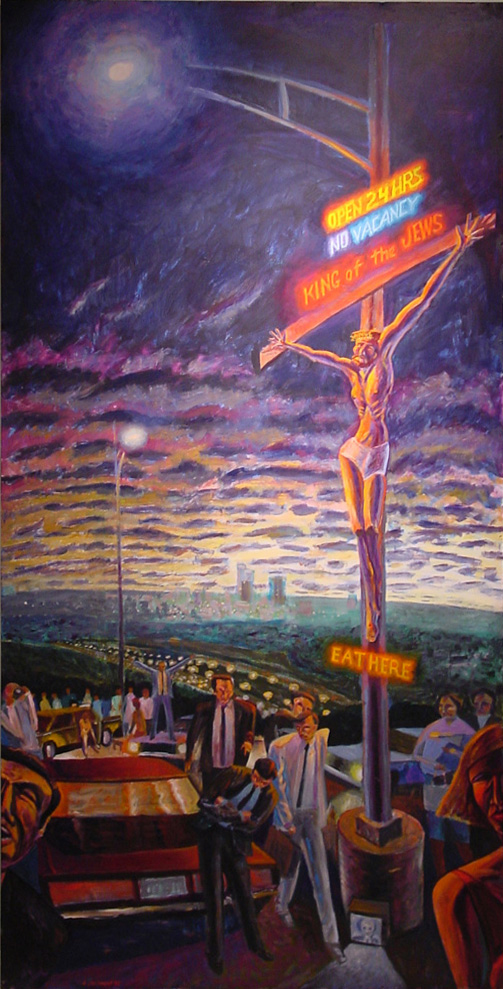

"Crucifixion at Barton Creek Mall"

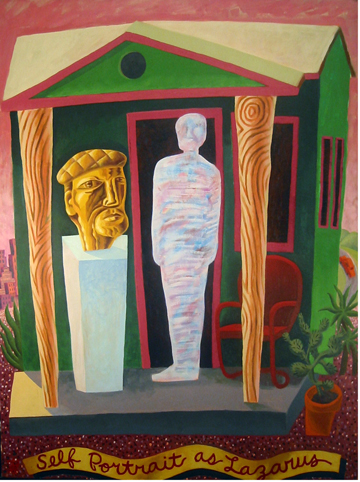

"Self-Portrait as Lazarus"

"Bus Stop", paintings by James Janknegt

In “Crucifixion at Barton Creek Mall” Christ hangs between neon signs in a lurid cityscape while bored, debauched looking citizens plan evening activities. “Eat Here” refers to the Eucharist and “Open 24 Hours” (a note to divine omnipresence) is ignored, as well as Jesus himself.

The painting caused a bit of a hoopla when the Austin bank president sponsoring the show accused him of being “sacrilegious” and demanded it be removed. In an interview with John Paul Davis, Janknegt describes how the entire show was then canceled by the curator and the incident landed on the front pages. Local Christian radio stations were besieged with angry callers decrying this “blasphemous painting.”

Janknegt denies blasphemy but feels crucifixion should be offensive and ugly now just as it was then.

“Initially there was no need to display the reality of the horrors of crucifixion, most Christians having a good chance of knowing someone personally who had been killed this way,” he reasons.

Centuries later the cross no longer symbolized “shame and utter annihilation,” but was only a symbol of hope. He charged that the cross had “become ubiquitous and innocuous, not representing suffering and shame or victorious life either.” Placing a dying Jesus in a parking lot recreates the scandal and “the symbol is re-energized,” he contends.

After perceiving the impossibility of making everyone happy, Janknegt made a decision: “If I had something of a spiritual nature to say, why not just say it? So I started doing more overt Christian subject matter but in the same style and set in contemporary Austin.”

At this time Janknegt moved from being a diagnostician of social problems to being a “celebrant.” Moving hard against the tide of received philosophy, he decided he had a fondness for the suburbs he had grown up in and used them as a metaphor for hope and domestic joy. Why not? Thus Jesus is baptized in a city park, a trashcan stands for sins, and handsaws and key chains host holiness or at least stand for it.

This necessitated a change in style also, as he couldn’t realistically depict dozens of tract homes at once. That and the need to express the transcendent, outside of proper space/time brought Janknegt a closer look at icons and medieval imagery as well as properties of cubism. From this grew a 1998 show, “Suburban Interiors and Other Apocalyptic Paintings.”

Striving to make his work accessible by people who are literate in the “basic Bible stories,” Janknegt rules out making work so personal it becomes inscrutable.

“I try to be very careful about the images and symbols I use to stay true to the content of the biblical message,” he says.

Janknegt’s work from the 1990s is more stylized, a cross between cubism with art deco buildings and occasional Latin touches. Janknegt carried his religious works into a new atmosphere. With remarriage and increasing domesticity, his surroundings are more meaningful.

"Easter Morning" by James Janknegt

Joyous and light “Easter Morning” (1992) exemplifies Janknegt’s move from dark heart of urbania to a more personal and optimistic place. Flowers explode like fireworks, a great fish spouts Jonah into a vase and a gardener tends topiary beasts and bunnies in the shade. He adds to his iconic vocabulary.

Portraits are rare as rhinos in his work, particularly self-portraits. An exception is “Self-Portrait as Lazarus,” presenting two unorthodox possibilities: a standing mummy as Lazarus may have emerged from the grave, neither dead nor alive; and a great gold-plated head on a pedestal, a bit of a confession, apparently.

In what appears to be a family barbeque to the biblically illiterate, “Three Visitors” reenacts one of the most mysterious passages in all Scripture. Abraham entertains three men as if they were merely cousins but recognizes he is speaking to the Ha Shem himself. Just stopped to chat – and negotiate for millions of souls in Sodom and Gomorrah over the ribs.

Janknegt uses the mundane, trivial and domestic to illustrate mystical concepts and narrate Bible stories. He’s in good company, as Crivelli adorned Magdalene in Italian brocades and Gauguin places costumed Breton women at the crucifixion.

“Jesus used everyday imagery in his parables, not overt religious symbols,” Janknegt explained before one of his exhibits. “The beauty of the parables is located in their ambiguity; he leaves them open-ended. Each generation needs artists who are willing to translate his imagery so that the stories can be ‘owned’ again.”

Overt politics and social campaigning are treated subtly or avoided – although “Slaughter of the Innocents” is clearly about abortion. “Prophet’s Dream” is one of those obscure pieces, where winged faces of all U.S. presidents hover about a sleeping man who is approached by an angel.

Janknegt may avoid politics but expressed open dismay at some contemporary art philosophy.

He explains, “I moved from Naturalism through images of contemporary life mingled with religious imagery to express more than the materialistic notions of a physical world.”

Janknegt also avoids a trap in modern art that “believes that art should only be about art drowning in self-referentialism” – or art for art’s sake only.

A material world is replaced with a sacramental view of the cosmos and a great, overarching story shot through with personal tales and beliefs. On canvas Janknegt manipulates color and shape hoping to imply a larger narrative of God interrupting time and space.

Becoming a Roman Catholic years back has heavily influenced Janknegt’s art.

“I desire to re-establish painting in the great tradition of the Church before the Reformation and outburst of iconoclasm changed the art world forever” is his sweeping goal.

Not painstakingly recreating the old styles, but keeping with the spirit of Renaissance and earlier art. Most of the secular art world rarely ponders the demands of the Reformation anymore, and a percentage couldn’t even define it – but the Church is still duking it out.

Janknegt is remarkably prolific, churning out dozens of paintings each year as well as other full-time employment much of the time. He repairs his home and raises goats, chickens and vegetables and all make cameo appearances in his work. Jesus refers to all these in parables, almost a mystery to many in the 21st century; what does it means to build, shepherd, plant or harvest?

Over the last decade the painter turned to straight illustrations of biblical narratives, and he has many predecessors who came before him. Prints from his series of parables such as “Lazarus and the Rich Man” or “Treasure Field” are on his website.

Austin’s thriving art community hasn’t excluded the church. Janknegt mentions the many high-caliber Christian artists he’s worked with over the years.

Inquiring about art in the church itself, he revealed, “I feel (we are) accepted for the most part.”

Many churches there host exhibition spaces and local Episcopal and Presbyterian seminaries actively support artists.

About the art scene in Austin and religious art in particular, Janknegt optimistically mentions the surge of interest in contemporary “Christian” art: “I get a lot of encouragement over the Internet from people all over the world who respond to my work.”

What would Janknegt like to see? Rediscovery of a common, visual language stretched between traditions of Christian faith and contemporary life. He imagines a cross-disciplinary language, encompassing music, writing, poetry and the visual arts based on symbolism – or the visible world standing for the invisible.

“For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face” (I Cor 13:12).

Read more at http://www.wnd.com/2014/01/jesus-finds-his-way-to-texas/#PABGLygJXPlV6W6t.99